VIDEO LECTURE BY R. MARK MUSSER

Relating Environmental Fascism to Baalism and the End Times

THE ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS OF NAZI GERMANY & THE HOLOCAUST

By R. Mark Musser

The original enviro-Nazis were Nazis. Eco-fascism is no metaphor. It is rooted in German history like a giant oak tree with its sap filled with the Romanticism, Existentialism, Social Darwinism, and Neo-Paganism of the 1800’s and early 1900’s that eventually nourished the very oak leaves of National Socialism. For all of the historical nuances and/or differences that may exist between each one of these particular movements, they all have one thing in common – Nature knows best.

National Socialism was a nature based ethos that pioneered many important facets of what is today called environmentalism, everything from animal rights to nature preservation, from sustainable forestry to a green hunting policy, from Aryan sustainable development to environmental social engineering schemes over private property, from the preservation of wolves to a “back to the land” movement that later even dabbled with organic farming, from environmental spatial planning strategies to stormwater management. The Nazis even fooled around with an air pollution policy that attempted to require industry in the cities to pay for pollution damages it engendered on the countryside. Nazi environmentalism also played a horrific role in the holocaust itself where the wanton slaughter of human beings was deemed necessary in order to cleanse the landscape for German occupation in Poland, Belarus, the Ukraine and western Russia.

From Goethe’s Romanticism to Schopenhauer’s Environmental Ethics

In the heart of Buchenwald Concentration Camp lies an old stump of a huge oak tree that died during an allied air raid late in the war. Buchenwald means “Beech Forest.” When the Nazis originally cleared the ground for the construction of the camp, they saved the oak tree. It was known as Goethe’s oak. The famous titan of German literature, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), used to spend much time around the environs of this particular oak tree, the destination of his favorite forest. Goethe helped blazed the trail for the German Romantic movement that strongly opposed the Enlightenment’s emphasis upon logic, reason, and objectivity that allegedly led to all of the modern ills of the Industrial Revolution. In place of such values, Romanticism advocated subjective experience, emotions, spirituality, and the natural world. Even though Goethe opposed the mechanistic emphasis of the Enlightenment sciences, he still considered himself to be a natural scientist – a veritable harbinger of environmental things to come.

More troubling, after complaining about “Jewish nonsense” from the Old Testament, Goethe once opined, “Had Homer remained our Bible, how different a form would mankind have achieved!” The German romance with nature thus began with a whiff of anti-Semitism that would become increasingly more virulent as time wore on. In fact, Goethe’s great emphasis throughout much of his writings was upon holism and the oneness of the natural world and the reconciliation of opposites that stood directly antithetical not only to the Enlightenment, but also to the Judeo-Christian worldview that presumed man to be made in God’s image, and hence above creation in a divinely ordained dualistic world. In Goethe’s romance with nature and the classical world, he popped the cork that would increasingly devalue human life in the face of an all-encompassing natural world which man is not allowed to rise above, no matter how impractical and cruel such a course of action might take.

Goethe was followed by other German romantic nature lovers who began ramping up anti-Semitism against the Jews for being anti-natural. Men like Ernst Moritz Arndt (1759-1860) and Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl (1823-1897), both of whom left the Christian ministry for the Romantic movement, nationalistically began to accuse the Jews for despoiling the landscape with their predatory control of the economy stemming from modern cosmopolitan cities completely devoid of hearty and healthy values that are to be learned from the forests and countrysides of Germany. Arndt wrote a famous poem during the Napoleonic Wars entitled “The German Fatherland” that starkly juxtaposed the progressive civilization of the French Enlightenment with the romantic fatherland of Germany.

Arndt viewed Industrial Capitalism based on the Enlightenment principles and run by Jewish finances to be an invasive destructive force upon the fatherland of Germany. Arndt’s protégé Riehl was even more anti-Semitic, xenophobic, and nationalistic. Riehl became the very ecological father of public forestlands, wetlands, nature preservation, and sustainable development. In particular, he extolled the virtues of the indigenous peasantry rooted in the land who stood opposed to the “rootless Jews” in charge of the cities, “Where large numbers of Jews reside, the population as a whole is almost always politically and economically fragmented. The Jewish huckster finds that his paltry capital circulates much more freely among the urbanized and small town burghers of central Germany than among the authentic peasants of the mountains or the plains.”[1]

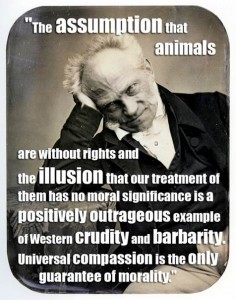

Even the great German thinker Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) held very similar pro-nature anti-Semitic views. Schopenhauer was one of the original gurus of both environmental ethics and animal rights. Most disconcerting, however, Schopenhauer charged that the source of the barbaric treatment of animals in Europe was to be found in both Judaism and Christianity. Closely related, he also rejected the Enlightenment’s conception of nature that emphasized it as a divinely created well-ordered machine.

Schopenhauer’s environmental ethics specifically targeted the domineering attitude towards nature and animals found in the Bible, especially from the opening pages of Genesis where God commanded Adam and Eve, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth, and subdue it; and rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky, and over every living thing that moves on the earth (Genesis 1:28).” Schopenhauer strongly believed such a Judeo-Christian domineering view over nature invariably led to animal cruelty. Shockingly, Schopenhauer spitefully said that Jewish animal cruelty demanded some form of European retribution, “We owe to the animal not mercy but justice, and the debt often remains unpaid in Europe, the continent that is permeated with the odor of the Jews.”[2]

More ominous still was Schopenhauer’s solution to the alleged problem. In order to save the animals, the Jewish view of nature must be banished from the European continent, “It is obviously high time in Europe that Jewish views on nature were brought to an end.”[3] He then threatened, “The unconscionable treatment of the animal world must, on account of its immorality, be expelled from Europe!”[4] Such was the conclusion of one of Germany’s most important geniuses of the 1800’s.

Worst of all, Schopenhauer was Adolf Hitler’s favorite philosopher. One of the first pieces of legislation passed by the Nazis in 1933 was an anti-Semitic animal rights law that forbid Jewish kosher slaughter. This practice was specifically highlighted in the climax of the infamous documentary drama entitled “The Eternal Jew” (1940) right before the Fuhrer showed up for the first time in the film. The narrator then lauds Hitler’s effort to bring to an end such “cruel” practices in Germany which then shades into his famous speech given in 1939 before a huge crowd of Nazis. Here, Hitler virtually lets everyone present know that he is about to send the Jews into hell on earth as he will insidiously hold them personally responsible if they initiate another global war with their international finances. At this, Hitler receives a rousing ovation.

Nietzsche’s Earth Based Existentialism

Schopenhauer was also the German bridge between Romanticism and Existentialism that completely countered the Enlightenment’s worship of reason with an emphasis upon nature and natural existence that trumped human thought and rationality. In particular, Schopenhauer supplanted Kant’s acceptance of the moral argument for God’s existence, otherwise known as the categorical imperative, with what he called “pity” where one’s humane attitude toward animals and nature should be extended to human beings as well. Furthermore, along such existential lines, Schopenhauer strongly believed the will of man was far more important than the thought of man in characterizing the true essence of a human being.

Schopenhauer’s student, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), then picked up where his teacher’s natural ethics ended, but with a vengeance. Nietzsche vehemently castigated Kant’s categorical imperative, the last vestige of God found in modern western philosophy. While Nietzsche fully agreed with Schopenhauer’s thesis that the human will was more important than thought, he rejected his doctrine on pity and humaneness that Schopenhauer advocated to curtail the instinctual excesses of the will. Nietzsche considered such an ethos as womanly and weak. As such, Nietzsche replaced Schopenhauer’s “pity” doctrine with his infamous “will to power” doctrine.

While Nietzsche was not anti-Semitic, he was extremely anti-Christian. Nature and philosophical existentialism were used by Nietzsche to disguise his hatred for Christianity since its heavenly emphasis mocked the earth and its real flesh and blood existence. Writing Thus Spake Zarathustra from the spectacular Engadine Alps in Switzerland, Nietzsche blurted out, “I beseech you my brothers, remain faithful to the earth, and do not believe those who speak to you of other worldly hopes!”[5] Nietzsche also added that since God was now dead, “To sin against the earth is now the most dreadful thing.”[6]

The existence of the earth is specifically used by Nietzsche to contrast it with heaven and its alleged corrupting otherworldly emphasis. Nietzsche’s infamous “God is dead” theology is inextricably bound up with this earthly existentialism. His so-called superman ethos is also cut from the same cloth. Nietzsche’s desire was to replace what he calls the Judeo-Christian slave morality of weakness and meekness with strong masculine values like heroism, strength, and courage. This is the heart of Nietzsche’s “beyond good and evil” doctrine, if not also his “will to power” creed.

Since God is dead, men must become supermen in order to legislate a new set of values for the future based on biology and instinct rather than upon western rationality. Western rationality has shown that God is dead. It therefore must be transcended by a new set of values in order to avoid the dangerous meaningless of nihilism. Since Nietzsche believed the weakest part of man was his consciousness, and that biology, body, willpower, and instinct were his strengths, these new set of values governing the future would have to transcend the Enlightenment. Nietzsche even recommended humanity must utilize state prescribed breeding programs in order to weed out the weak from the strong, and presumed that war and conflict were at the vortex of human evolution and growth. Thus, Nietzsche’s “will to power” was not an attempt to dominate nature, but was to be in accordance with nature, and rooted in an earth based evolutionary existentialism.

Heidegger’s Existential Environmentalism

Not surprisingly, the Nazis imbibed heavily from Nietzsche’s existential teaching. Next to Schopenhauer, Hitler’s second favorite philosopher was Nietzsche.[7] The Nazis essentially made the Nietzsche Archives of Weimar the official shrine of their regime. Here, existentialist philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976)[8] spent much time (1935-42)[9] Nazifying Nietzsche for National Socialist consumption. Even as late as 1944, Heidegger claimed that Nietzsche was the spiritual inspiration of Hitler.[10]

Heidegger was also a very enthusiastic Nazi environmentalist in the 1920’s and 30’s. His philosophical emphasis upon “being” or natural existential existence, helped lay the groundwork for what is today called deep ecology. In Heidegger’s philosophy, “being” itself trumps western rationality and thought. Heidegger once taught, “The Fatherland is being itself.”

Existentialism is thus very fertile ground upon which to develop an environmental philosophy. Existentialism uses natural existence or ‘being’ to trump idealistic or religious thought that heightens itself above the natural world. Nature and its holistic interrelatedness thus become trump cards to neutralize both philosophy and religious faith as inconsistent with what actually exists in the real world. Religious and philosophical thought needs to bow to nature and its existence, rather than try to arrogate itself above them through imaginary ideas and concerns, especially of the Christian theological variety.

For Heidegger, religious and western speculative thought invariably leads to a false, dominating view over nature, which has become especially superficial in the modern mechanized world. For Heidegger, therefore, what needs to be done is to destroy western philosophy and its Judeo-Christian handmaid. The main thrust of Heidegger’s political philosophy is to reduce all metaphysics to the question of ‘being’ or existence.[11] In so doing, western man’s alienating and destructive dominance over nature can be arrested.

The Missing Link of Ernst Haeckel’s Social Darwinism & Nature Worship

While German Existentialism hardened German Romanticism into a more respectable philosophy, it was Ernst Haeckel’s (1834-1919) evolutionary scientism that provided the final biological link between nationalism, socialism, race, nature protection, and ecology, all of which later became the bread and butter of National Socialism. Haeckel accomplished this by mixing up Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory with German racism together with a secularized form of nature worship. He thus presumed the Germans were on top of the evolutionary chain in terms of cultural progress. As such, Haeckel was also the father of German Social Darwinism. Incredibly, Haeckel believed his racialist brand of Social Darwinism was strictly based on sound biological science. He was the first scientist to view the Jews as a biological problem, and even coined the term ‘ecology’ in 1866.[12]

To Haeckel and those involved with his romanticized version of Darwinism, the name of their philosophical scientific system was called Monism. Today, Haeckel’s Monism is better characterized as Social Darwinism. The idea of Monism is taken from the Greek word “mono” which means “One.” The point of Monism, therefore, is to emphasize unity, holism, or oneness. German Monism or Social Darwinism was a romantic-pantheistic-holistic view of man and nature that attempted to explain everything from within the context of nature alone without any reference to a transcendental deity or sacred text. It took holism so seriously, that the transcendent nature of both man and God were denied. The dualistic relationship between man and nature was rejected. Man was seen as completely rooted into the natural world and subject to its evolutionary biological laws without exception. Nature was thus king, if not deified into a feudalistic natural order.

In other words, Haeckel reconciled religion with science by cutting out the Judeo-Christian worldview and it’s God. Haeckel wrote, “The Monistic idea of God which alone is compatible with our present knowledge of nature, recognizes the divine spirit in all things … God is everywhere … Every atom is animated.”[13] At this juncture, German evolutionary pantheism thus replaced the belief in traditional theism. Haeckel thus transferred the creative powers of the God of the Bible to the pantheistic powers of Nature itself. Haeckel also suggested that his pantheism was a polite form of atheism.

In his Social Darwinian Monism, Haeckel emphasized that Nature itself and Nature alone was the sole basis for the evolutionary development of plants, animals, and society as well. The primacy of Nature also dictated the spiritual and political life of people as well. Haeckel’s romanticized Monism was thus a totalitarian Darwinism because it was used as a total explanation for just about anything and everything, including politics. Through Haeckel’s biological evolutionary worldview with strong ecological predilections, Nature was completely politicized.

Nazi Environmentalism in Germany

By the 1930’s, Romanticism, Existentialism, Social Darwinism, and Neo-Paganism helped promote a nature based ethic that fully displayed itself with new environmental rules under the banner of National Socialism. German ecology became politicized under Nazi biology. The German greens had finally found a political platform in the biologically based Social Darwinism and natural existentialism of the Nazi Party. Theirs was a voice which had been so often neglected during the social-democratic days of the Weimar Republic in the 1920’s, but was finally overturned with the political fortunes of the Nazi Party.

As such, the connection between the early German greens and Nazis was strongly intertwined indeed. Whereas only 10% of the German population belonged to the Nazi Party, between 60% and 70% of the greens in various conservationist groups were Nazi Party members. As such, Nazi Germany actually began in a green cloak. In the early to mid 1930’s, the Third Reich emphasized a brand new era of political ecology. In fact, Nazi Germany was the greenest regime on the planet.

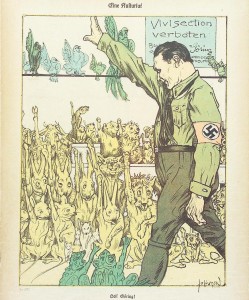

Even the Nazi leadership widely represented all of the differing facets of the early German green movement. The Fuhrer himself was a self-proclaimed animal lover who also claimed to be a vegetarian. From 1933-35, Hitler signed very significant environmental legislation. In 1933, he signed an animal rights law that initially tried to ban vivisection altogether. In 1934, he signed a green Nazi hunting law that was the first of its kind in the western world. In 1935, Hitler signed the Reich Nature Protection Act, otherwise known as the RNG, that went well beyond the setting aside of nature protection areas, but also included environmental social engineering schemes over private property, especially with regard to construction activities. With the RNG came what are today called environmental impact statements, initially described as environmental effects reports. Field Marshall Herman Goering (1893-1946) was also actively involved in the passing and administration of these laws, as well as putting into practice sustainable forestry strategies called Dauerwald, which means “Eternal Forest.”

The greenest of the Nazi hierarchy was Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s secretary up until 1941. Even propaganda minister, Joself Goebbels, was a vegetarian. Hess was followed by the infamous SS leader Heinrich Himmler, who was a green pagan mystic, animal lover, and vegetarian. Himmler and the SS dreaded over what they called “land flight.” Himmler and his agricultural mentor, Richard Walther Darre, actually believed German racial biology was being destroyed by the cosmopolitan life of the cities. Germans were being uprooted from their homeland and enslaved to the artificial values of the Jewish international market on the one hand, and Jewish Bolshevism on the other. Himmler opined “The yeoman on his own acre is the backbone of the German people’s strength and character.” [14] To counteract this existential crisis, Darre and Himmler came up with a cockamamie racial green doctrine called “Blood and Soil.” The idea was to get German blood back out of the city into the soil of the countryside where they could become self-sufficient farmers in a ‘buy local’ scheme of racist proportions.

Dr. Fritz Todt was appointed Inspector General for the German Roadways by Hitler and built the Autobahnen. Todt was sympathetic to ecological ideas and early environmental engineering experiments. Dr. Todt became the leader of the Nazi construction industry. Hitler’s architect, Albert Speer, who replaced Todt after he was killed in a mysterious plane crash in 1942, held very similar views to Todt. With such men, including the SS, involved as they were constructing a new Germany, came a compromise between German industry and environmentalism that is today everywhere trumpeted as sustainable development. Sustainable development was essentially born in the Third Reich as the Nazis blended their racist ideas, i.e., blood, with environmentalism, i.e., soil. Even Goering’s Four Year industrial war plan was supposed to be regulated by new environmental spatial planning strategies and policies.

Master Planned Communities, Landscape Cleansing & Genocide on the Eastern Front

Many green historians are quick to judge Nazi environmental plans as unserious and unrelated to the overall National Socialist program. They also strongly maintain that Nazi environmentalism was completely compromised by the industrial Four Year Plan together with all of the ecological destruction brought on by the war itself. The Nazis themselves, however, viewed things much differently. They saw the war as a necessary means to a noble end. What the Nazis began to do on the Eastern Front in the early part of World War II strongly suggests their environmental plans were not going to be dropped, but rather be reinforced, if not strengthened after victory was secured.

What the Nazis wanted most of all was lebensraum, which literally means “living space.” A quick, decisive victory over Russia promised the Germans a strong position in what would certainly become a new world order. With their own lebensraum in the east, this would allow the Nazis to compete with the American-Anglo industrial complex without having to resort to the corrosive effects of what they deemed to be international Jewish capitalism. More importantly, they could become self-sufficient with plenty of land in the east to be used for growing food and for sustainable industrial development under Nazi state control that could later be extended throughout the entire Reich.

Hitler believed if Germany controlled the continent of Europe along with western Russia, he could control the world. Closely connected, Hitler also believed Germany was grossly overpopulated and running out of natural resources. As far as Himmler’s SS was concerned, there was not enough space in Germany itself to re-ruralize the population of Germany “back to the land.” In other words, without more “living space” there could be no proper marriage between German blood and soil. Additional lebensraum was required. It would therefore be sought in Eastern Europe and western Russia.

During the war, the SS had grandiose plans to use research garnered from the Office of Spatial Planning to create an eco-imperial empire in the conquered eastern territories. Inspired by SS planners Konrad Meyer (1901-1973), Emil Meynen (1902-1994), and Walter Christaller (1893-1969), sustainable development as an applied political policy was to be implemented on the eastern front behind advancing German lines. The SS planned to use industry in the conquered eastern territories along with slave labor to pay for and build master planned communities that were, in fact, very green. The plan was called General Plan Ost (East).

As one of the great spoils of war, landscape planners were not beset by any foreign constitution, laws, regulations, or private property. They were given absolute freedom to plan to their hearts content. In fact, Nazi expert planners called it “planning freedom”[15] Some Nazis believed the occupied East was an urban and environmental planners’ paradise where all of the sins of landscape development of the past could be ameliorated. Landscape planners rushed into the annexed territories with climatic-geographical surveys and “transfer of population” exhibits in their hands, ready for implementation. Such landscape planning was called a “total landscape plan” where cities would be redone, village areas would be emptied, farms destroyed, and people either deported or killed or both. Landscape Planner Heinrich Friedrich Wiepking Jurgensmann (1891-1973), who was the chair of the Institute for Landscape Design at the University of Berlin, wrote in 1939 that the war in Poland promised “a golden age for the German landscape and garden designer that will surpass everything that even the most enthusiastic among us had previously known.”[16]

Worst of all, behind enemy lines, the living space of Poland, Ukraine, Belarus, western Russia and the Baltics would be cleansed of unnatural Jews and Slavs who were unworthy of the soil they lived on. Thus, racial genocide coincided with landscape cleansing. The Nazis justified the forced removal of thousands of Poles from their homes on the grounds that such an allegedly degenerate race of people could never have a proper relationship to nature and those portions of the countryside occupied by the Germany army.[17] Rebuilding beautiful cities, green landscape plans, sustainable development, renewable energy programs, nature reserves, botanical and organic farms, fox recovery programs – even inside concentration and death camps – it’s all here in the most grisly set of circumstances imaginable.

Emil Meynen, one of the primary geographers and environmental spatial planners working for the SS, attended the infamous Wanssee Conference in 1942 where the destruction of the Jews was discussed from a technocratic point of view. Eliminating the Jews was certainly a top priority in order to prepare the groundwork for total landscape planning. Environmental planners were also well aware of the existence of concentration and death camps.[18] By cleansing the landscape of inferior races through a massive euthanasia program, the eastern territories could then be used to help rebuild the natural rural health of the German people. In fact, environmental degradation was used to justify the ethnic cleansing of people not properly suited to their natural surroundings. In short, the Jews, Poles and Russians were not properly related to nature and thus deserved to be liquidated.

Sacrificial Nazi Oaks

There is a luxuriant oak tree standing just inside the gated entrance into Auschwitz where the sign reads “work makes you free.” In fact, the immediate area around the Auschwitz entrance is populated by giant oak trees. There are also oak trees in the immediate proximity of the gas chambers and crematoriums as well. More ominous, the gas chamber doors at both Auschwitz and Treblinka were often made of solid oak. The intimate proximity of such oak symbolism to concentration and death camps like Buchenwald and Auschwitz is not likely to be merely coincidental. There was a certain method to the Nazi madness. That Adolf Eichmann was placed in charge of the logistics of the holocaust in the eastern territories is incredibly ironic. His last name virtually means “man of the oaks.” No matter how technocratic the gas chambers may have become by 1942, the ancient symbolism of human sacrifice and nature worship being practiced under the oak trees (Isaiah 1:29-31; 57:1-8; 2 Kings 17:28-41; Hosea 4:11-13) bleeds through the veneer of Nazi modernism.

In his youth while attending architectural school in Vienna in 1908, Adolf Hitler wrote up a play about religious sacrifice centering on the differences between Christianity and German Paganism. In fact, he feverishly spent all night working on it. When his roommate, August Kubizek, was awakened, he asked Adolf what he was doing. Kubizek wondered what Adolf could possibly be working on, and what would be the end result of all of his work. Was Adolf’s architectural school that difficult? Hitler did not respond to him, but instead gave him a piece of paper with these word written on it, “Holy Mountain in the background, before it the mighty sacrificial block surrounded by huge oaks; two powerful warriors hold the black bull, which is to be sacrificed, firmly by the horns, and press the beast’s mighty head against the hollow in the sacrificial block. Behind them, erect in light-colored robes, stands the priest. He holds the sword with which he will slaughter the bull. All around, solemn, bearded men, leaning on their shields, their lances ready, are watching the ceremony intently.”[19]

Astounded by Hitler’s passion, Kubizek asked him what it was. Hitler finally responded, “A play.” Kubizek, of course, was mystified by the connection between the play and his architectural studies, “Then, in stirring words, he described the action to me. Unfortunately, I have long since forgotten it. I only remember that it was set in the Bavarian mountains at the time of the bringing of Christianity to those parts. The men who lived on the mountain did not want to accept the new faith. On the contrary! They had bound themselves by oath to kill the Christian missionaries. On this was based the conflict of the drama.’[20]

While some may be surprised by Hitler’s anti-Christian stance in the play here, it must be kept in mind the Fuhrer often complained about how Christianity made Judaism universal. Hitler’s play was borrowed from the ariosophist Guido von List’s Die Armanenschaft der Ario-Germanen published earlier in the same year.[21] Guido von List (1848-1919) believed in a pan-German nature mysticism called Ariosophy. Ariosophy simply means “wisdom of the Aryans.” It was both anti-modern and anti-Semitic, and mixed apocalypticism, occultic mythology, paganism, racism, evolution, eugenics, and ecology into its worldview. Kubizek said that in addition to philosophers Schopenhauer and Nietzsche, Hitler also loved German mythology as well.[22]

That Adolf Hitler would later rule Germany from the spectacular Bavarian Alps at his mountain chalet in the Obersalzberg fits in perfectly with his play that he wrote up many years earlier. Many of Hitler’s plans were envisaged up in the Bavarian Alps where he spent much time brooding over the mountain landscape. Could it be that Hitler believed that he was protecting Germany as a pagan mountain priest or shaman? When Kubizek wrote his book after the war, he sensed that there was something very significant that particular night when Hitler wrote up his play. Looking back on it, he sensed that it had a strong connection to what later became known as the holocaust. Could it be that paganism, mountains, nature worship, oak trees, and human sacrifice are hiding behind the shadows of the firelight blazing around the camp of National Socialism?

ENDNOTES

[1] Heinrich Wilhelm Riehl, Natural History of the German People, translated by David Diephouse, (Lewiston/Queenstown/Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1990), 84.

[2] Arthur Schopenhauer, Parerga and Paralipomena: On Religion, volume 2, translated from German. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), 372.

[3] Ibid., 375.

[4] Ibid., 377.

[5] Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spake Zarathustra: A Book for None and All, translated by Walter Kaufmann. (New York: Penguin Books, 1966, 1954), 13.

[6] Ibid.

[7]Kubizek, August. The Young Hitler I Knew, (Maidstone, United Kingdom: George Mann Limited, 1973, 1954), 134-136.

[8] In The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany, (Cambridge University Press, 2006), Frank Uekoetter calls Martin Heidegger one of the who’s who of German conservationism in 1934, 93.

[9] Emmanuel Faye, Heidegger: The Introduction of Nazism into Philosophy in Light of the Unpublished Seminars of 1933-1935, (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2009), 252.

[10] Ibid., 105.

[11] Ibid., 249.

[12] Ernst Haeckel coined the term ‘ecology’ in 1866 in his Generelle Morphologie.

[13] Ernst Haeckel, Monism as Connecting Religion and Science. The Confession of Faith of a Man of Science, London, 1894, p. 28 quoted by Gasman, The Scientific Origins of National Socialism, (Transaction Publishers, 2004), 65.

[14] Heinrich Himmler: Volkische Bauernpolitik, undated, Central Archives, Microfilm 98.

[15] Wolschke-Buhlman, “Violence as the Basis of National Socialist Landscape Planning” in How Green Were the Nazis?: Nature, Environment, and Nation in the Third Reich, edited by Franz-Josef Bruggenmeier, Mark Cioc, and Thomas Zeller. Athens: Ohio University Press, 247.

[16] Friedrich Heinrich Wiepking-Jurgensmann, “Der Deutsche Osten: Eine vordringliche Aufgabe fur unsere Studierenden,” Die Gartenkunst 52, 1939, 193 quoted in Wolschke-Buhlman, “Violence as a Basis of National Socialist Landscape Planning,” in How Green Were the Nazis?, 246-47.

[17] Closmann, “Legalizing a Volksgemeinschaft” in How Green Were the Nazis?, 34

[18] Ibid., 249.

[19] Kubizek, 110.

[20] Ibid., 110-11.

[21] Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and Their Influence on Nazi Ideology, 1890-1935, (New York: New York University Press, 1985), 199.

[22] Kubizek, 135-37.

Copyright 2014 R. Mark Musser

Permission is herewith given to copy and distribute by electronic or physical means as long as it is not sold – the copyright notice is included and credits are given to the author. This article was originally published in the Spring 2014 edition of Jubilee: Recovering Biblical Foundations for our Time (Editor – Joseph Boot).