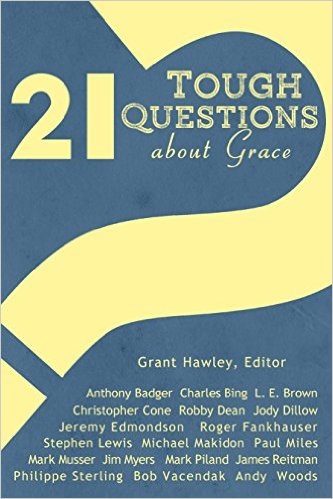

One of the more difficult controversies found on the pages of the Gospels is over what is called the Unpardonable sin spoken by the Lord Jesus Christ himself. Mark’s presentation on this difficult subject was presented at Chafer Theological Seminary in 2015 when the book, “21 Tough Questions on Grace” was featured.

THE UNPARDONABLE SIN

By Mark Musser, M. Div.

The unpardonable sin is otherwise known as the blasphemy of the Spirit. It is specifically mentioned in the parallel passages of Matthew 12:30-32, Mark 3:28-30, and Luke 12:10. It is conspicuously absent from the book of Acts and the Epistles, which strongly suggests the limited time frame in which this particular sin could be committed. Jesus Himself is the originator of the unpardonable sin. Before singling out the great danger of committing the blasphemy of the Spirit directed toward some Pharisees who attributed His powers of exorcism to Satanic activity, Jesus takes great pains to describe the height, length, width, and depth of His forgiveness toward any and every other sin (Matthew 12:31; Mark 3:28-30). The unpardonable sin is therefore a singular and extraordinary category of unbelief that is anchored in the Gospel period when the historical Jesus walked the earth. It cannot be committed today. Dr. Lewis Sperry Chafer sharply writes, “When considering the subject of the blasphemy of the Spirit, it may well be noted that, quite beyond human explanation, men do not swear in the name of the Third Person. From this fact, it may be concluded that there is now and ever has been a peculiar sanctity belonging to the Holy Spirit. His very name and title implies this.”[1]

The Consequences & Unparalleled Uniqueness of the Blasphemy of the Spirit

The gravity of the unpardonable sin is self-evident. It is no ordinary sin. Mark 3:28 and Matthew 12:31 uses the term “blasphemies” and “blasphemy” to distinguish it from the word “sins” and “sin” in order to accentuate its heinous character. According to the BDAG Lexicon, the noun “blasphemy” means “reviling” or “denigration” or “disrespect” or “slander.” Mark 3:29 uses the verb “blaspheme” to characterize Matthew’s and Luke’s phraseology that reads “speak against” (Matt 12:32; Luke 12:10). While Matthew warns the unpardonable sin cannot be forgiven either “in this age, or in the one coming,” Mark summarizes and heightens the enormity of the slander by following up his usage of the verb “to blaspheme” with this terrifying phrase coming from the mouth of Jesus Himself, “But he is guilty of an eternal sin.” In its original context, the blasphemy of the Holy Spirit is clearly understood in Matthew and Mark as an unforgivable sin which will have “eternal” consequences in the judgment to come.

Such a blasphemous sin is sharply contrasted with every other sin possible, including blasphemy against the Son of Man – all of which Jesus specifically says are forgivable, “Therefore I tell you, every sin and blasphemy shall be forgiven people. And whoever speaks a word against the Son of Man will be forgiven” (Matt 12:31-32). Mark summarizes, “Truly, I say to you, all sins will be forgiven the children of man, and whatever blasphemies they utter …” (Mark 3:28). However, in great contrast to the boundless frontier of God’s most gracious forgiveness, Matthew, Mark, and Luke all agree the blasphemy of the Spirit “cannot be forgiven.” The uniqueness of this particular sin therefore needs to be respected.

The Blasphemers of the Spirit

Matthew, Mark, and Luke all identify the blasphemy of the Spirit as attributing Jesus’s miraculous powers of exorcism to Satan (Matt 12:24; Mark 3:22, Luke 11:15). Most specifically, it was certain Pharisees who were warned about the great danger of committing the unpardonable sin. This is further substantiated by Matthew and Mark who both use the relative pronoun to write, “he who” or, “the one who.” Luke’s individual application is stronger as he uses the singular articular participle to write, “the one blaspheming the Spirit.” While “he who” could possibly refer to national Israel,[2] the most natural interpretation is that Jesus is warning certain individuals of the blasphemy of the Spirit. Indeed, while the crowds were astonished at both the teaching and the miracles of Jesus (Mark 1:14-3:20), some religious leaders or “scribes” (Mark 3:22) from Jerusalem were becoming more hostile toward Him and His ministry, particularly because of His miraculous powers. Matthew then identifies these particular scribes from Jerusalem as “Pharisees” (Matt 12:24). They were thus particular scribal or scholarly Pharisees who were well schooled in Jewish traditions and the Old Testament.

The Pharisees were the religious separatists and moralists of the Gospel period who believed themselves to be exceptionally zealous in keeping the Mosaic Law. They were the Old Testament scholars of the day in both Jerusalem and in the local synagogues. While some Pharisees did believe in Jesus (Matt 3:7; John 19:38-39), most did not (Matt 23:13; John 12:42). The greatest opposition that Jesus faced was from the Pharisees and other religious and political leaders of Israel.

Early on, all three synoptic gospel writers declare Jesus received the Holy Spirit (Matt 3:13-17; Mark 1:9-12; Luke 3:21-22) promised by Isaiah the prophet (Isaiah 11:1-3; 61:1-2), which confirmed his Messianic credentials. This occurred at His baptism when He was anointed by John the Baptist to be the Messianic King of Israel (John 1:26-36). Jesus was thus supernaturally empowered by God to do miracles as one of the proofs that He was indeed Israel’s Messianic King (John 5:36; 10:25, 37-38; Mark 2:1-13). Yet this incredible Messianic testimony was willfully rejected by the disbelieving Pharisees and other religious leaders of Israel (John 7-8; 11:47-57). The religious leaders of Israel utterly failed to recognize the Holy Spirit’s powerful ministry at work in the life of Christ.

While many people, including the Pharisees, were eyewitnesses of all the various miracles that Jesus had performed in Galilee (Mark 1:23-28, 32-34; 3:11-12), one exorcism that was performed in the very presence of some Pharisees receives special notice which leads to the warning of the unpardonable sin. “Then a demon-oppressed man who was blind and mute was brought to him, and he healed him, so that the man spoke and saw. And all the people were amazed, and said, “Can this be the Son of David?” But when the Pharisees heard it, they said, “It is only by Beelzebul, the prince of demons, that this man casts out demons” (Matt 12:22-24). This is precisely where the Pharisees come dangerously close to either committing the unpardonable sin, or have already committed it (Matt 12:31).

As the original historical context strongly indicates, the unpardonable sin was an exceptional sin that was very difficult to commit. Jesus even exposes the contradictory reasoning processes the Pharisees had to go through to arrive at such a conclusion that the exorcistic powers of the Son of God were from the devil, “Every kingdom divided against itself is laid waste, and a divided household falls. And if Satan also is divided against himself, how will his kingdom stand? For you say that I cast out demons by Beelzebul” (Luke 11:17-18).

In Mark 3:27, Jesus presses further their inconsistency, “But no one can enter the strong man’s house and plunder his property unless he first binds the strong man, and then he will plunder his house.” Jesus Himself, of course, is the Man who is in the process of plundering Satan’s property. If Satan, the “strong man” is being robbed of people, i.e., “his property” (Eph 2:1-3; Heb 2:14-15), then who except the Messiah could possibly be stronger? This means Jesus must be stronger than Satan, “But when one stronger than he attacks him and overcomes him, he takes away his armor in which he trusted and divides his spoil” (Luke 11:22). The fact that Jesus is performing exorcisms means the long awaited “Seed of the woman,” who is explicitly prophesied to defeat the Serpent going all the way back to Genesis 3:15, has now finally come to Israel.

Jesus’s argument against the Pharisees is both simple and flawless. It is much easier to accept the “finger of God” (Luke 11:20) is at work in Jesus, than to complicate the matter by trying to suggest He is performing exorcisms through the power of Satan. Furthermore, since Jesus has entered Satan’s house and bound him, this has opened the door for others to join in on the exorcism spree which was just witnessed back in Luke 10 when Jesus sent out the 72 disciples to preach and perform miracles. Their ministry included the power to perform exorcisms (Luke 10:17).

Luke’s discussion about the successful ministry of the 72 disciples amidst the various cities of Galilee (Luke 10:1-20) also helps explain the final argument that Jesus used against the Pharisees, “And if I cast out demons by Beelzebul, by whom do your sons cast them out? Therefore they will be your judges. But if it is by the finger of God that I cast out demons, then the kingdom of God has come upon you” (Luke 11:19-20).

While many scholars have tried to suggest the exorcisms the “sons” of the Pharisees are performing (Luke 11:19) were Jewish exorcists akin to the ones recorded in Acts 19:11-17, this is very unlikely. In Ephesus, the sons of the Jewish high priest Sceva were unsuccessful in their exorcism (Acts 19:14-17), whereas Jesus affirms the reality of the exorcisms being performed by “your sons” (Luke 11:19). “Your sons” is, therefore, far more likely a reference to the miraculous ministry of the 72 disciples that was just performed in their midst from Luke 10.[3] This would also explain better why such exorcists will become the judges of the Pharisees.

Either way, the Pharisees are caught. If their “sons” exorcise demons, the 72 disciples themselves will judge the Pharisees. However, if Jesus casts out demons by the Spirit of God (Matt 12:28), this will be far worse for the Pharisees. It will mean nothing short of the fact that the Old Testament Messianic Kingdom has “come upon” them in a most surprising judgment. Shockingly, the presumed experts of the Law failed to recognize Jesus as the Messiah of the coming kingdom prophesied throughout the Old Testament who is in their very midst going so far so as to perform exorcisms to prove it. As such, the phrase “the kingdom of God has come upon you” has a “threatening sense. Since they set themselves in array against it, it is an enemy which has surprised them, and which will crush them.”[4]

Not only have the Pharisees rejected the ministry of the 72, which Luke 10:10-16 declares is bad enough, but they have since done something far worse. By Luke 11:14-26, they are calling the ministry of the Son of God a veritable nest of demonism run by the prince of demons in the face of incontrovertible evidence that the power of God is miraculously at work in the very acts of Jesus Christ. While blasphemously calling Jesus “Satan” is forgivable, attributing His miraculous works of exorcism to demonic activity is not. This is precisely where the blasphemy of the Spirit, the warning of the unpardonable sin, is unloaded upon the Pharisees.

The twisted and convoluted reasoning of the Pharisees is therefore fully exposed in all of its contradictory madness that will merit a special judgment from God known as the unpardonable sin. While the “people marveled” at the exorcism that Jesus performed (Luke 11:14), almost to the point of worshiping Him, the Pharisees callously threw cold water on this spectacular demonstration of power and authority, “He casts out demons by Beelzebul, the prince of demons” (Luke 11:15). These particular Pharisees rejected the obvious truth that only the Son of God could perform such miracles. Worse, they came up with an outlandish conspiracy theory that defied logic by attributing satanic powers to Jesus instead.

How the Insane Rejection of Messianic Evidence Led to the Blasphemy of the Spirit

One of the remarkable features about the unpardonable sin pericope is that it divulges the extent of just how far men can go in their rejection of Jesus Christ. Their unwillingness (John 5:40) to believe Jesus was the Messiah overrode their ability to critically evaluate the obvious evidence that they had just witnessed the Son of God remove a demon from a mute man. Since the Pharisees could not deny the reality of the exorcism(s), and yet would not accept Jesus as their Messiah, they had to come up with a counter argument. Instead of acknowledging Him as the Son of God, the Pharisees inconsistently attribute His miraculous power over demons as a sign of being possessed by Satan.

The Pharisees were far more willing to accept contradictory conspiracy theories than admit that Jesus was the promised Messiah of the Old Testament. More troublesome, these particular Pharisees from Jerusalem were propagating this conspiracy theory to the crowds in order to cast doubts in their minds as to what they just witnessed (Mark 3:22). This is when Jesus argues before everyone present about the absurdity of the Pharisaic assertions. Jesus then follows up by warning the Pharisees of the perilous danger of committing the blasphemy of the Spirit (Mark 3:23-30; Matt 12:22-45; Luke 11:14-12:10).

Although the text only warns of the unpardonable sin, and is silent as to whether or not anyone actually committed it, it is very likely that some Pharisees crossed the threshold of blaspheming the Spirit. In Matthew 23, Jesus literally blasts them into Hell with a condemnatory sermon of exceptional fervor right before He was crucified, “But woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! You lock up the kingdom of heaven from people. For you don’t go in, and you don’t allow those entering to go in” (Matt 23:13). The Pharisees, therefore, as the representatives of the nation who were highly influential in the religious life of Israel, are particularly culpable with regard to the national rejection of Messiah that led to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD. God judges shepherds and teachers by stricter standards (Jeremiah 23:1-40; James 3:1). Jude even characterizes false teachers as being “doubly dead,” which literally reads “dead twice.” (Jude 12)

Later on in Matthew 23, Jesus criticizes the Pharisees for traveling far and wide to make their disciples “twice as fit for hell” (Matt 23:15) as they themselves are. In Matthew 23:24, He accuses them of straining at gnats while swallowing camels, echoing the same irrational inconsistency some of them demonstrated when they claimed Jesus exorcised demons by the power of Satan.

Indeed, the whole point of the miracles of Jesus Christ, especially His incredible power to perform exorcisms, was designed to prove to the people of Israel that He was the Messianic Son of God predicted by the Old Testament Scriptures (Acts 2:22). Everyone knew that Jesus performed miracles. Even King Herod asked Jesus to do a miracle (Luke 23:8). The very Pharisees who witnessed Jesus remove the unclean spirit from the blind and mute man could not refute the facticity of the exorcism. Rather than question the actuality of the exorcism itself that was so obvious to all, they had to say that Jesus was performing such miracles by satanic powers in order to deny their significance. When hostile opponents make such admissions, this is usually the best kind of evidence one can only hope for in a court of law.

The exorcisms of Jesus cornered the Pharisees. In truth, the exorcisms were an ultimatum. The Pharisees must either accept Jesus as the Messiah, or sacrifice reality, common sense, and even their reason in order to deny it. When the Pharisees began to say that Jesus was doing His miraculous powers of exorcism by the power of the devil, they demonstrated their obstinate unbelief to the fullest extent that is without remedy. God had done everything possible for such men so they could easily believe that Jesus was the Messiah by affording them the best possible circumstances and evidence imaginable this side of the grave. Yet the Pharisees willfully refused to believe that Jesus was the Christ in the face of overwhelming proof that strongly confirmed otherwise. The obstinate sinful willpower of these Pharisees sacrificed their faith, reason, and common sense in order to avoid the obvious conclusion that Jesus was truly their Messiah. The blasphemy of the Spirit is therefore a special category of unbelief reserved specifically for certain Pharisees, who, in light of their knowledge of Judaism and as guardians of the Old Testament Law, were granted the best possible opportunity to believe in Christ, but shockingly, were unwilling to do so (John 5:44-47).

Many more people since the gospel period have believed in Christ with far less testimony afforded them. While Thomas demanded evidence of the resurrection (John 20:25), and was even granted it (John 20:26-29), he did not fail to believe when He finally saw the resurrected Christ, “My Lord and my God!” Jesus then responded, “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed.”

The Gospel period provided mountains of evidence that showcased Jesus Christ was indeed the Messiah, all of which is summarized in John 5:30-40. The first witness Jesus calls to the stand is God the Father Himself (John 5:32). The second witness Jesus calls up is the ministry of John the Baptist (John 5:33-35). The third witness Jesus mentions is His miraculous power given to Him by God the Father (John 5:36-38). The final witness Jesus showcases is the Old Testament itself, “You search the Scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life; it is these that testify about Me” (John 5:39). The life and ministry of Jesus Christ could easily be backed up by countless Old Testament prophecies and Messianic types the Pharisees had all grown up with and knew all too well.

The religious leaders of Jerusalem, including the Pharisees, marginalized the testimony of John the Baptist (Luke 20:1-8). They ignored the testimony of the Old Testament (John 5:39-40, 46-47). They also rejected the incredible teaching ministry of Jesus Christ that testified of His divine nature (John 7:15, 45-47). They willfully overlooked His miracles by complaining that Jesus broke the Sabbath by healing people on Saturdays (John 5:1-18). As the evidence of Jesus’s Messianic credentials mounted, their own sinful wills trumped their faith and reason that was supposedly informed by the Old Testament so they were unable to come to the obvious conclusion that Jesus was the Messiah.

Such a sustained sinful and stiff-necked opposition eventually led many Pharisees to a dead end in which they will find themselves surrounded and cornered by a mounting body of evidence that Jesus was the Christ. This would first find expression in their persecution (John 7:13) directed toward anyone who “confessed Him to be the Christ” by excommunicating them from the synagogues (John 9:22). It would later find further expression in their growing murderous rage against Jesus (Luke 6:6-11) which broke the very Mosaic Law they claimed to uphold and represent (John 5:45; 7:49-52).

This is precisely the point that Jesus presses during the controversy at the Feast of Tabernacles as the people debate back and forth over whether or not He is the Christ (John 7:11-12, 40-43), “Did not Moses give you the Law, and yet none of you carries out the Law? Why do you seek to kill Me?” (John 7:19). Their sinful unwillingness reaped a hateful madness so that some of the Pharisees went so far to claim that Jesus was performing exorcisms by the power of Beelzebul. In short, their hatred will turn them into absolute fools as they reject the most obvious for incomprehensible conspiracy theories that defy common sense.

The Pharisees thus show themselves to be completely unqualified to judge for the nation on whether or not Jesus was the Christ. What started out as criticisms that Jesus was a Sabbath breaker, and then later “a gluttonous man, and a drunkard, a friend of tax-gatherers and sinners” (Luke 7:34) grows ever greater so some of them charge Him with blasphemy, and finally take the incomprehensible position that He exorcises demons by the power of Satan. Here, some Pharisees, privy to an actual exorcism, cross the point of no return from which there is no recovery. They attribute the miraculous powers of the Holy Spirit, which from a strict evidential point of view testifies of their divine origin, to the devil. Such a continual rejection of divine testimony over an extended period of time finally culminates in what is known as the unpardonable sin or blasphemy of the Spirit.

The Law of Moses was judgmental enough. Once the historical revelation of the Son of God is added on top of the condemnatory conditions of the Mosaic Covenant, the culpability of the religious leaders of Israel becomes an unparalleled liability so that a most severe judgment will be unleashed upon them if they fail to believe. With greater privilege comes greater responsibility (John 9:39-41).

The Timeframe of the Blasphemy of the Spirit

This means the blasphemy of the Spirit cannot be committed today precisely because Jesus Christ is not on the earth performing miracles and exorcising demons to substantiate His claims that He is the Messiah. The physical and historical revelation of the Son of God in fulfillment of many Old Testament prophecies coupled together with the judgments of the Mosaic Law itself, can only lead to compound sin if people refuse to believe it, especially if one is a religious leader like the Pharisees most certainly were. This is certainly the primary reason why Jesus can later charge the religious leaders of Israel with “all the righteous blood shed on the earth” from Abel to “Zechariah, son of Berechiah, whom you murdered between the sanctuary and the altar” (Matt 23:35).

More to the point, in the historical context of the unpardonable sin (Luke 11:14-22), Jesus Himself alludes to the unparalleled uniqueness of His presence on the earth that will single out His particular generation to be exceptionally liable with regard to accepting Him as the Messiah (Luke 11:29-32). In Luke 11, some religious leaders demanded that Jesus perform a heavenly sign for them (Luke 11:16), even though they had just witnessed the blind and mute man being exorcised of a demon. They apparently wanted to witness the apocalyptic miracles of the Second Coming of Christ, something which Jesus sharply denied them, “This generation is an evil generation. It seeks for a sign, but no sign will be given to it except the sign of Jonah. For as Jonah became a sign to the people of Nineveh, so will the Son of Man be to this generation. The queen of the South will rise up at the judgment with the men of this generation and condemn them, for she came from the ends of the earth to hear the wisdom of Solomon, and behold, something greater than Solomon is here. The men of Nineveh will rise up at the judgment with this generation and condemn it, for they repented at the preaching of Jonah, and behold, something greater than Jonah is here” (Luke 11:29-32).

Twice, Jesus singles out His own particular generation from the days of King Solomon and Jonah the Prophet. The point is clear. If the Queen of Sheba, a Gentile, came from afar to hear the wisdom of Solomon, which was based on second hand reports, then what will God expect from Israel if the Son of God actually walks among them performing miracles to demonstrate His Messianic credentials, especially if He can exorcise demons? Is not Someone greater than Solomon ministering in their midst? Likewise, if the people of Nineveh, who belonged to the evil Gentile kingdom of Assyria, repented at the preaching of a disobedient Jonah, then what will God expect from Israel if God’s only-begotten Son personally comes and preaches in their synagogues? Is not Someone greater than Jonah’s preaching in their midst? The Pharisees, in particular, should have been able to identify this obvious reality from the Old Testament and proclaim to the people of Israel that the Messiah has come.

Jesus clearly tied the warning of the unpardonable sin together with the uniqueness of His own Gospel time period that was greatly distinguished from other eras of the Old Testament. He thus singled out the religious leaders of Israel, especially the Pharisees, as being particularly culpable precisely because of the concentrated amount of divine revelation that was given to them (Matthew 12:41-42). They prided themselves in the very Old Testament that predicted the coming of Messiah, and yet when He finally came, they indict Him with demonism by claiming His powers of exorcism were inspired by the devil.

In the historical person and presence of Jesus Christ, the Messianic miracles predicted by the Old Testament and the condemnatory consequences of the Mosaic Law came together into an explosive mixture that has not been seen before or since. Dr. Jay Vernon McGee clarifies, “Sheer logic leads us to see that if in the days of Christ’s presence on the earth – to attribute His miracles to the power of Satan rather than to the power of the Holy Spirit, was to commit the unpardonable sin, then conversely, his absence today makes it impossible for us to commit the unpardonable sin and our position is entirely consistent with a “whosoever will” Gospel.”[5] Dr. Lewis Sperry Chafer tersely concludes, “The possibility of this particular sin being committed ceased with Christ’s removal from the earth.”[6]

The Post Gospel Period

That the unpardonable sin is limited to the Gospel period is further substantiated by the book of Acts when Stephen was martyred (Acts 7:58-8:1). Stephen was a man full of faith and the Holy Spirit (Acts 6:5). He was an outstanding preacher of the gospel and a performer of great miracles in the sight of the people which angered the religious leaders of Israel who opposed his teaching (Acts 6:8-10). Stephen was then seized and placed before the Sanhedrin to defend himself against false charges (Acts 6:11-15). After Stephen gave a rousing sermon on Old Testament history and prophecy that implicated the religious leaders of Israel for breaking their own law (Acts 7:1-53), the Sanhedrin went mad and rushed upon him like a pack of wild dogs and stoned him to death (Acts 7:55-57).

While it is possible that some of the religious leaders from the Sanhedrin may have already committed the unpardonable sin going back to the gospel period, it still must be pointed out that Stephen prayed God would forgive them for stoning him to death (Acts 7:59-60). Stephen’s prayer was most certainly answered in the conversion of the great persecutor of the early church (Acts 8:1-4; Gal 1:13-14; 1 Tim 1:13), Saul (Acts 9), who later became the apostle Paul. Paul even understood himself not only to be a former blasphemer, but also to be the chief of all sinners, i.e., the worst of all sinners (1 Tim 1:13-14). The point being, that if God can forgive Paul, he can forgive anyone (1 Tim 1:15-16). In addition, while Stephen himself was filled with the Spirit and could even perform miracles (Acts 6:5-8), he did not charge his listeners with the blasphemy of the Spirit in his sermon, but rather rebuked them for “always resisting the Holy Spirit” (Acts 7:51) as they so often did throughout the Old Testament (Isaiah 63:10-14). This means that even Christians empowered by the Holy Spirit to do miraculous signs cannot precipitate the charge of the blasphemy of the Spirit. Only the Messiah’s personal testimony at the time of His ministry on the earth to Israel can instigate the charge of the blasphemy of the Spirit precisely because He alone is the Son of God.

As such, by the time of the Jerusalem Council, even a sizable portion of the Pharisees had actually become believers (Acts 15:5). There is no more mention of the unpardonable sin in either the book of Acts or in the epistles as is historically witnessed during the gospel period. Dennis Rokser confirms, “It is interesting to note that after this event the Bible never again utilizes the phrase, ‘the blasphemy against the Holy Spirit’ to describe a future event or to underscore a person’s rejection of Jesus Christ. This phrase is limited to Israel’s national rejection of Jesus Christ in these events recorded during Christ’s earthly ministry.”[7] Furthermore, the epistles of the New Testament were written to believers rather than unbelievers. Believers cannot lose their salvation (John 6:35-40; 10:27-30), and therefore cannot commit the unpardonable sin since they are everywhere described as a forgiven people. They may grieve and quench the Spirit (Eph 4:30; 1 Thess 5:19), but they cannot blaspheme the Spirit.

The Unpardonable Sin & Unlimited Atonement

It is tempting to teach, as Jesus even seems to suggest in the pericope of the unpardonable sin, that the doctrine of Unlimited Atonement applies to all sin with the one exception of the blasphemy of the Spirit (Matthew 12:31; Mark 3:28-29). Others have sometimes even associated contemporary unbelief in the Messiah as a more modernized version of the unpardonable sin that can still be committed during the church age if people fail to believe in Christ. Such views, however, overlook the unique historical circumstances behind the unpardonable sin, and also fails to appreciate that Jesus did indeed die for all the sins of the entire world – whether past, present, or future (John 1:29; 1 John 2:2) – including the sin of unbelief and the blasphemy of the Spirit. The New Testament clearly teaches that all sin was nailed to the cross (2 Cor 5:14-21).

However, as is self-evident from the Scriptures, the death of Christ and the unlimited extent of the atonement does not mean that everyone will believe in Christ. While the debt of sin has been fully paid for on the cross, and in principle, the penalty of sin has also been accordingly removed, the spiritual experience of that forgiveness is mediated through faith and grace (Eph 1:7-8; 2:1-9). Thus, while the extent of the atonement is unlimited because of the perfect person and work of Jesus Christ on the cross (Col 2:8-15), the application of its benefits is clearly restricted to those who believe in the cross and resurrection of the Son of God (John 8:24; Acts 13:26-39). Toward the end of Paul’s sermon given at Pisidian Antioch, Paul proclaims the “forgiveness of sins” to the synagogue (Acts 13:38), but then points out, “and through Him everyone who believes is freed from all things, from which you could not be freed through the Law of Moses (Acts 13:39).” Paul thus points out that only those who have believed are freed from “all things” in terms of the actual experience and possession of the forgiveness of sins.

While various bible scholars may struggle to explain concretely some of the nuances of this paradox that the salvation experience of unlimited atonement is only given to those who believe, 2 Corinthians 5:14-21 comes closest to resolving this apparent spiritual conundrum. In 2 Corinthians 5:14, Paul categorically teaches unlimited atonement when he writes, “having concluded this, that one died for all.” Yet in the following verse, Paul distinguishes “they who live,” i.e., believers (2 Cor 5:15), from unbelievers, who the apostle describes elsewhere as dead in their “trespasses and sins” (Eph 2:1). Without the regenerating power of the Holy Spirit that is initiated by faith (John 3:1-16; Acts 11:12-18; Eph 1:13; Rom 5:5; Titus 3:4-8), unbelievers are still dead in their sins in spite of the fact that such sins have been paid for on the cross. The law of sin and death that is rooted in the Original Sin of Adam and the Fall (Genesis 2:16; 3:15; Rom 5:12-14; 7:23) can only be annulled by a higher law, which Paul calls the “law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus” in Romans 8:2. The personal application of this higher law of the life giving regenerating power of the Holy Spirit is limited to those believe in Christ (Rom 3:23-5:5).

Yet in spite of the doctrine of Unlimited Atonement that teaches the judicial penalty for sin has been removed through the crosswork of Christ, more than a few verses in the New Testament still speak of retribution (2 Thess 1:8-10), punishment (2 Pet 2:9), divine vengeance (Deut 32:34-35), and much deserved judgment (Rev 16:5-7) against wickedness and sin (Rom 3:10-19), in which the unregenerate are storing up wrath for themselves wherein God “will render to each person according to his deeds.” (Rom 2:5-6) Paul even warns, “there will be tribulation and distress for every soul of man who does evil (evil = sin), of the Jew first, and also of the Greek.” (Rom 2:9) Paul then reminds his Roman readers of the impartiality of God (Rom 2:11) which will be on full display “on the day when, according to my gospel, God will judge the secrets of men through Christ Jesus.” (Rom 2:16) How can there be a remaining liability for sin when Jesus fully paid for it on the cross? In truth, the same problem remains for believers as well, who will stand at the judgment seat of Christ (1 Cor 3:10-15) in which “he who does wrong will receive the consequences of the wrong which he has done, and that without partiality.” (Col 3:25) This particular problem is actually more acute precisely because Christians have already been forgiven their sins, and in this particular instance, the doctrine of Limited Atonement does not resolve the theological problem.

Regardless of the some of the theological difficulties here, while it is true the judgment of the cross does indeed include every last sin as far as the extent of the atonement is concerned, which certainly complicates the whole discussion about how God will judge the world, at the end of the day, sinners are still the residents of Hell, and saints the residents of Heaven (John 5:28-29). While John says, “He who believes in Him is not judged; he who does not believe has been judged already, because He has not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God,” (John 3:18), he adds further, “This is the judgment, that the Light has come into the world, and men loved the darkness rather than the Light, for their deeds were evil (sinful). For everyone who does evil hates the Light, and does not come to the Light for fear his deeds will be exposed.” (John 3:19-20) In other words, as unbelievers are dead in their sins, this still means they are morally culpable and liable for their sins even though Christ has died for them. John even demonstrates how their sins prevent them believing in Christ.

Perhaps in the same way that believers inherit rewards in heaven for obedience even though they are already justified by God through the cross, it stands to reason that unbelievers will merit retribution in Hell for their disobedience as Jesus Himself intimates, “Do not marvel at this, for an hour is coming, in which all who in the tombs will hear His voice, and will come forth, those who did the good to a resurrection of life, and those who did the evil to a resurrection of judgment.” (John 5:28-29) More to the point, if the sanctification of Christians can “fill up that which is lacking in Christ’s afflictions” (Col 1:24), then perhaps, conversely, the sins of unbelievers will somehow store up extra retribution (Rev 18:4-8) to finish off what was wanting at the judgment of the cross with regard to the holy justice of God?

In light of some of these difficulties with regard to the doctrine of Unlimited Atonement, Scripturally speaking, it is thus perhaps still better to teach that if the work of Christ is rejected by unbelievers, they have thus refused the payment for sin, and so will still be left with a debt they cannot possibly afford to pay on their own. Dr. Chafer remarks, “to reject Christ and His redemption, as every unbeliever does, is equivalent to the demand on his part that the great transaction of Calvary shall be reversed and that his sin, which was laid upon Christ, shall be retained by himself with all its condemning power. It is not asserted here that sin is thus ever retained by the sinner. It is stated, however, that since God does not apply the value of Christ’s death to the sinner until that sinner is saved, God would be morally free to hold the sinner who rejects Christ, as being accountable for his sins, and to this unmeasured burden would be added all the condemnation which justly follows the sin of unbelief.”[8]

In Chafer’s view of Unlimited Atonement, he reminds his readers the cross is not the only saving instrumentality.[9] While the cross is most certainly the object of faith, faith is still required to make the transaction effectual, “The value of Christ’s death is applied to the elect, not at the cross, but when they believe.”[10] While those who believe in Limited Atonement complain the saving benefits of the cross must be actual, and not merely potential if it is to be considered a truly finished work, Chafer acutely points out, “It is actual in its availability, but potential in its application.” Chafer thus does not deny the unlimited reality of the atonement, but still maintains its potentiality because faith is also a critical component on how a person is saved.

It seems the great tragedy and insanity of the unbeliever is that he will have hell to pay even though his sin debt was fully paid for as he willfully refused the payment that was to be credited to his account on the basis of God’s gracious goodness and justice as exhibited in the cross of Christ. In short, the old adage that one can bring a horse to water, but cannot make him drink, seems to explain some of the difficulties of Unlimited Atonement far better than esoteric theological explanations that have a hard time acknowledging how sinners are still liable for their sins (Matt 5:22). While theology may struggle[11] to explain the relationship between Unlimited Atonement and the ongoing liability of sin (John 9:41), in truth, there is no contradiction between Jesus warning the Pharisees of the unpardonable sin as they push the limits of willful unbelief to new heights never before witnessed in the history of the world, nor seen since that time, knowing full well His future act on the cross would pay for that particular sin. Dead men do not even receive payments, much less make them, and therefore will not be released of the obligations they still owe. As Chafer notes, “The impenitent of this age are judged according to their own specific sins, since the value of Christ’s death is not applied to or accepted for them until they believe.”[12]

ENDNOTES

[1] Chafer, Lewis Sperry. Systematic Theology, Doctrinal Summarization, Volume 7, (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications), 1976 (1948), p. 48.

[2] Dr. Arnold Fruchtenbaum holds the unpardonable sin is not an individual sin, but national, and that the judgment itself refers to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD. In an article entitled “The Rejection of His Messiahship,” Dr. Fruchtenbaum argues that national Israel “refused to accept Jesus as the Messiah because He did not fit their pharisaic mold or idea of what the Messiah was supposed to say and do. Their alternative explanation as to how He was performing His miracles was to say that He Himself was possessed by Beelzebub the prince of demons. This, then, became the official basis of the rejection of the Messiahship of Yeshua. The Messiah responded to this accusation by telling them that their statement could not be true because it would mean that Satan’s kingdom was divided against itself. And Yeshua proceeded to pronounce judgment upon the generation of that day. That generation had committed the unpardonable sin: blasphemy of the Holy Spirit. The unpardonable sin was the national rejection of the Messiahship of Yeshua while He was physically present on the grounds that He was demon possessed. This sin was unpardonable, and judgment was set. The judgment came forty years later in A.D. 70 with the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, followed by the worldwide dispersion of the Jewish people. The Pharisees were stunned by this pronouncement of judgment. They tried to retake the offensive in verse 38 by demanding a sign, as though the Messiah had done nothing so far to substantiate His Messiahship! But in Matthew 12: 39, there was a change of policy regarding His signs. While the Messiah would continue to perform miracles even after chapter 12, the purpose of His miracles had changed. No longer were they for the purpose of authenticating His Person and His message in order to get the nation to come to a decision. The leaders had already made that decision. From this point onward, there would be no more signs for the nation, except one: the sign of Jonah, the sign of resurrection.”

[3] D.L. Bock, Luke Volume 2: 9:51–24:53. Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic 1996), pp. 1077-78.

[4] F.L Godet, A Commentary on the Gospel of St. Luke, (New York: I. K. Funk & co. 1881), Luke 11:20-22.

[5] Jay Vernon McGee, Matthew, Volume 1, (LaVerne, CA: El Camino Press, 1975), p. 124.

[6] Chafer, p. 48.

[7] Rokser, Dennis. Shall Never Perish Forever: Is Salvation Forever or Can it Be Lost? (Duluth, Minnesota: Grace Gospel Press, 2012, p. 234.

[8] Chafer, Systematic Theology, Volume 3, p. 196.

[9] Ibid., pp. 193-94.

[10] Ibid., p. 197.

[11] In The Atonement and Other Writings, (Corinth, Texas: Grace Evangelical Society, 2014) Zane Hodges argues, “What is the bottom line? It is this: Men are not sent to hell for their sins. They are sent there because they are not listed in the Book of Life. But the death of Christ does not cancel the law of sowing and reaping. When people are dead in trespasses and sins go to hell, they are eternally reaping what they have sowed,” p. 37. While there is certainly much truth in what Hodges says here, one major weakness of his position is that he certainly leaves the impression that God puts people in Hell simply because their names are not in the Book of Life – which opens up the door that God is capricious in His judgment, and therefore not just, because justice against sin is no longer a consideration as to why people will spend eternity in the Lake of Fire. In his zeal to make Unlimited Atonement ‘actual’ at the point of the cross rather than effectual by faith in Christ, Hodges is perhaps unwittingly creating bigger problems than what he has purportedly resolved.

[12] Chafer, Systematic Theology, Volume 3, pp. 197-98.

ENDNOTES

[1] Chafer, Lewis Sperry. Systematic Theology, Doctrinal Summarization, Volume 7, (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Publications), 1976 (1948), p. 48.

[2] Dr. Arnold Fruchtenbaum holds the unpardonable sin is not an individual sin, but national, and that the judgment itself refers to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD. In an article entitled “The Rejection of His Messiahship,” Dr. Fruchtenbaum argues that national Israel “refused to accept Jesus as the Messiah because He did not fit their pharisaic mold or idea of what the Messiah was supposed to say and do. Their alternative explanation as to how He was performing His miracles was to say that He Himself was possessed by Beelzebub the prince of demons. This, then, became the official basis of the rejection of the Messiahship of Yeshua. The Messiah responded to this accusation by telling them that their statement could not be true because it would mean that Satan’s kingdom was divided against itself. And Yeshua proceeded to pronounce judgment upon the generation of that day. That generation had committed the unpardonable sin: blasphemy of the Holy Spirit. The unpardonable sin was the national rejection of the Messiahship of Yeshua while He was physically present on the grounds that He was demon possessed. This sin was unpardonable, and judgment was set. The judgment came forty years later in A.D. 70 with the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple, followed by the worldwide dispersion of the Jewish people. The Pharisees were stunned by this pronouncement of judgment. They tried to retake the offensive in verse 38 by demanding a sign, as though the Messiah had done nothing so far to substantiate His Messiahship! But in Matthew 12: 39, there was a change of policy regarding His signs. While the Messiah would continue to perform miracles even after chapter 12, the purpose of His miracles had changed. No longer were they for the purpose of authenticating His Person and His message in order to get the nation to come to a decision. The leaders had already made that decision. From this point onward, there would be no more signs for the nation, except one: the sign of Jonah, the sign of resurrection.”

[3] D.L. Bock, Luke Volume 2: 9:51–24:53. Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic 1996), pp. 1077-78.

[4] F.L Godet, A Commentary on the Gospel of St. Luke, (New York: I. K. Funk & co. 1881), Luke 11:20-22.

[5] Jay Vernon McGee, Matthew, Volume 1, (LaVerne, CA: El Camino Press, 1975), p. 124.

[6] Chafer, p. 48.

[7] Rokser, Dennis. Shall Never Perish Forever: Is Salvation Forever or Can it Be Lost? (Duluth, Minnesota: Grace Gospel Press, 2012, p. 234.

[8] Chafer, Systematic Theology, Volume 3, p. 196.

[9] Ibid., pp. 193-94.

[10] Ibid., p. 197.

[11] In The Atonement and Other Writings, (Corinth, Texas: Grace Evangelical Society, 2014) Zane Hodges argues, “What is the bottom line? It is this: Men are not sent to hell for their sins. They are sent there because they are not listed in the Book of Life. But the death of Christ does not cancel the law of sowing and reaping. When people are dead in trespasses and sins go to hell, they are eternally reaping what they have sowed,” p. 37. While there is certainly much truth in what Hodges says here, one major weakness of his position is that he certainly leaves the impression that God puts people in Hell simply because their names are not in the Book of Life – which opens up the door that God is capricious in His judgment, and therefore not just, because justice against sin is no longer a consideration as to why people will spend eternity in the Lake of Fire. In his zeal to make Unlimited Atonement ‘actual’ at the point of the cross rather than effectual by faith in Christ, Hodges is perhaps unwittingly creating bigger problems than what he has purportedly resolved.

[12] Chafer, Systematic Theology, Volume 3, pp. 197-98.