“Musser’s Nazi Oaks” by William Kay

The Ignorant Fishermen’s Blog Review of “Nazi Oaks”

Nazi Environmentalism: How Green Were the Nazis? by Dr. Ileana Johnson Paugh

ALAN CARUBA’S BOOKVIEWS OF THE MONTH – NOVEMBER 2010

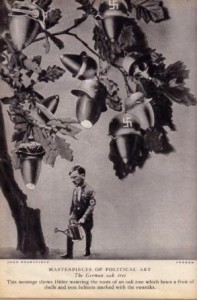

“Nazi Oaks” by R. Mark Musser is one of those important books that is unlikely to get the kind of mainstream media coverage it deserves because it draws on history to reveal how the Nazi regime in Germany during the 1930s was “the greenest regime on the planet,” driven by the same Green agenda that foisted the greatest fraud in the modern era, the global warming hoax. Musser is a pastor, a 1998 graduate of Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington. In 1994 he received a Master of Divinity and spent seven years as a missionary in Belarus and the Ukraine. His book documents the way the Nazi regime exploited a “return to nature” myth to capture the imagination of the Germans of that day and since the oak was a symbol of nationalism, Hitler ordered that thousands be planted all over the Reich. The practice was dubbed by Nazi environmentalists as “concordant with the spirit of the Fuhrer.” Hitler was an animal rights advocate, an environmentalist, and a vegetarian. He joined the ranks of the world’s greatest mass murderers guided by these views. What is most frightening are the parallels between the Nazi regime and the practices and views expressed by today’s environmentalists, many of whom share a contempt for humanity seeking a huge reduction in the world’s population as the key to “saving the planet.”

Copyright 2010 by Alan Caruba

NAZI OAKS BOOK REVIEW by Bruce Walker

It is odd, really more like eerie, how similar many of the fetishes of dead totalitarian systems of the last century are to the curiosities of modern leftism. The Nazi war on tobacco, for example, mirrors modern jihads against smoking, which invariably portray tobacco companies as evil. Mussolini, the leader of Fascism, prided himself on not smoking or drinking, just as Hitler, the leader of Nazism did, who was also a vegetarian. (Winston Churchill, by contrast, drank, smoked, and ate copiously.)

Nazis bragged early about putting into the horrors of concentration camps those who committed cruelty to animals. Fascists in Italy also pointed out to the world that their system of totalitarianism was solicitous of the welfare of animals. There was, in Italy, a “Fascist Society for the Protection of Animals” and the Fascists took early steps to preserve endangered animal species.

One overlooked area in which Nazism and modern leftism converge is the worship of nature, the expansion of a gentle and loving appreciation of divinely created beauty into an obsession bordering on religious fanaticism. Mark Musser, in his new book, Nazi Oaks, Advantage Inspirational, not only explores the historical development of radical environmentalism within the Nazi movement but he explains how this totalitarianism is grounded in a violent rejection of the historical Judeo-Christian worldview, which views nature as a blessing created for man by God. The Old Testament, as Musser explains, has an historical and a metaphysical prelude to problems which we associate with modern and thoughtful secularism.

The decline of faith accelerated with the infatuation with nature, which characterized the Romantic Period. The author notes the idealization of a holistic harmony of man with his environment which Henry David Thoreau urged and which was inextricably tied to hostility to the basic beliefs of Christianity, held in contempt by Thoreau with its Creator which exists outside of nature.

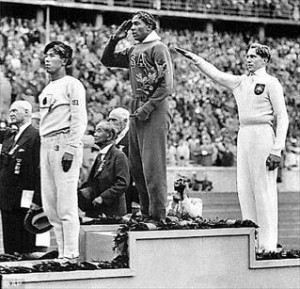

The Nazis adopted this attitude even before they came to power in Germany. In 1931, the National Socialist Physician League, for example, proclaimed the importance of national biology over national economy. After Hitler came to power, at the 1936 Berlin Olympics, he presented an oak seedling to each of the gold medal winners, including Jesse Owens, and these were taken back by the winners and planted as gifts from the German people.

The ghastly racial policies of the German were, in fact, an integral part of the holistic worship of nature which was at the heart of Nazi spiritual values. Nazism in Germany was preceded and nourished by a line of Germans who vehemently rejected Judeo-Christian metaphysics and, instead, worshipped the natural world. Two hundred years ago, Germans were complaining about the destruction of the natural environment of Germany.

This abhorrent philosophy blossomed in Nazi Germany. Environmental planning was made part of Nazi construction projects. Some Nazis actually proposed a “de-industrialization” of Germany, while organic gardening was practiced throughout Germany, including, horribly, in Auschwitz. Nazis taught schoolchildren about ecology and set aside almost 800 nature protection areas before the Second World War began.

The high water mark for Nazi environmentalism was in 1935 with the passage of the Reich Nature Protection Law called the Reichnaturschutzgesetz. The national office created by this law required “environmental effect reports” before conducting any project that might affect the landscape. The power of these Nazi environmentalists was enough to slow or stop activities related to the war effort.

Musser correctly draws the linkage between a pagan, Nazi Germany and the sort of pagan worship of nature which we experience in our world today, long after the Nazis had been consigned to their sector of historical Hell. And he shows us how environmentalists today who have studied the Nazis (looked, in effect, in the mirror) have tried to minimize the clear path of German anti-Christian romanticism through the Third Reich and into our political debate and moral arguments today. The book is well worth reading and it is a valuable reference on the evolution of radical environmentalism today.

Copyright 2010 by Bruce Walker on the Canada Free Press